In Exile 2: Goêtic Ethos

[For chapters one to three, please read the first part of this essay.]

By way of brief recapitulation: for twenty-five years, I’ve tried to live as a bridge between the wild realms of animistic ritual practice and the scripted routines of corporate work life. This essay is a raw self-note born from that tension; it's a reminder that the pain from the small world of wage labor is what enables truly great magic, as it shapes our character, and the way we learn to hold us in the world. More pragmatically, wage labor is quite a safe learning laboratory, that makes the truly dangerous work beyond it possible.

In this second part we are taking a closer look at the small world of everyday work life — and how we can come to life in it in ways that bear genuine magical authenticity. As much as possible, we will explore this through the lens of the spirits we work with, as goêtic practice is essentially about creating interspecies subculture with spirits — not attracting utilitarian gain for humans. Finally, at the end I am sharing a detailed break down of my own goêtic ethos; not meant for carbon copying but for kicking against and testing out in your own life.

LVX,

Frater Acher

May the serpent bite its tail.

IV.

To arrange ourselves with the small world means to accept that it won’t go away. Ever. If you can read this, your childhood is long over. And every day after, even once you are retired, will not exclusively, but to a great deal be about dealing with the matters, demands and turmoils of the small world.

The best advice I ever received for arranging ourselves with the small world was given to me by one of my teachers who I never met in the flesh. The twentieth-century author and occult initiate Gustav Meyrink had a central theme for all the magical books he wrote. In German it reads “Hüben und Drüben zugleich — ein ganzer Mensch”, and roughly translates as “Here and there at once — a whole human being.” Meyrink’s lifelong aspiration, expressed throughout his literary oeuvre, was to be fully present, awake, and active both in the spiritual or inner realm and, simultaneously, in the mundane or outer world. When we read his biography, we can learn a lot about the techniques and practices he found to turn this aspiration into a personal reality. Far ahead of his time, he shunned rigid either–or approaches, yet pursued an uncompromising personal yoga practice — at times spending entire nights seated in asana on a Prague park bench. As his example reminds us, extreme measures in our practice need not imply extreme aims in shaping the kind of presence we wish to embody in the world.

Our task, then, is to stand in both worlds at once — the small and the big — and to acknowledge, only then, that we have become both magician and adult, goês and wage-earner, a whole human being.

As such, experiencing the cage of the small world does not indicate that we have lost our path, but that at least we are moving forward on one side of our helical work. Feeling the double sense of insufficiency - to not yet be here and there at once — is not a flaw or failing, but a sign that we are following the ascent of the snakes around the pillar of the Caduceus from both sides. It shows that we are engaged in the painful work of healing ourselves.

Sometimes it can help to say this out loud:

Things are hard right now, and that is not because I’ve done wrong. This burden is not the fruit of my mistakes. Trouble won’t vanish, only because I take the blame. I will keep refining my responses, testing new versions of myself, widening the circle of choices. But I remain anchored in the knowledge that trouble will always walk with me. No chapter of life will be pure bliss; unless I abandon all aspiration. I pledge to myself: I will pull back from any needless suffering only to claim the purity of the martyr; and yet, I won’t flinch when the next ugly lessons appears on the horizon.

But how, then, is our path to be shaped? When there are no rigid rules, no handbook, no elders of an order to instruct us in the right way of wandering between the great and the small world? When even pain is no longer a sure sign that we must change direction? By what do we orient ourselves beneath so vast a horizon of life?

This question has occupied me for a long time. It stirs me every day — though less and less in relation to myself. Approaching fifty years of age, and having spent almost thirty of them upon the practical occult path, I have at least learned to recognize some of the signs and omens that serve as my own waymarks. What moves me now is the question of how to hand over what I have found — to others, to you. How does teaching actually work when your path will differ so radically from mine? How can I offer seeds that will take root in the soil where you stand? How can I avoid a tone that hardens into new orthodoxy or decays to a mere set of goêtic manners? In short: which lessons of my goêtic life might enrich yours?

What I feel confident enough to share is this: The tension of living in exile from where you think you belong, is a foundational human condition. Over the course of millennia, it made us come up with all sorts of spiritual theories, fantasies and daydreams. But what is real and true and here with us, is the sense of becoming estranged to ourselves. We are not in this world to always feel at home. We are not here to simmer in comfort but to accept hardship as a companion on stages of our life’s journey. Like our own shadow. Discipline or laziness, devotion or ignorance, none will cut that shadow off; no choices we can pursue will cut us out of that cage of the small world for good.

Some insist that “we are what we do,” claiming that deeds outweigh words, dreams, or ideals. Taken literally, this would reduce identity to a single flat dimension: every act in the small, physical world would define us as purely mundane, and every act in the big, inner world as purely spiritual. Judged by that standard alone, the maxim collapses into complete nonsense.

Humanity is little more than a vast membrane. Each of us is but a small part of that membrane. As such, it is not in our organic nature to lock things away, to seal and separate the self from the other. Our nature is, rather, to regulate a healthy permeability. We are, so to speak, bridge-wardens, determining to some extent what may pass through the membrane of our own bodyminds. Some passengers will engage and listen to us as wardens; others will just stomp over the bridge anyway. Our craft and art is not only to find ways to engage, to liaise and negotiate with as many passengers of the bridge of our bodyminds as possible. We can also develop the power to call or send away particular passengers. We not only give way (on a good day), but we also ring a bell and light a fire, for others to hear and see the passage that we are - between the small and the big world, between the outer and the inner realms.

To learn to recognize ourselves as bridge wardens — to understand our lives as being in service of all kinds of passage — is the vital work of the goês. This work calls us to act and explore in both the big and the small world. On a good day, we may use ritual to choreograph a particular crossing — our own or another’s — from here to there. On any ordinary workday, we are still engaged in the same labour of enabling passage, only on a different stage, with different actors around us.

Yet here lies the danger: just as we can fall into routine in our wage labor, so we can adopt hollow routine in our ritual work. On a slightly more polemical day, I might say that ritual is canned spirituality. We take up our ritual tools, open the can, and out comes exactly what it says on the label — tomato soup or pickled meat. This approach to magical thinking quickly degenerates into a capitalist logic of marketable structures, resource acquisition, and instant gratification.

On a calmer day, I would disagree with myself and argue instead that some rituals — the more advanced forms — grant access to cans without a bottom. They become thresholds into experiences that far transcend the ritual’s written outline. Here rituals forge new relationships.

Yet whichever view one takes, the essential point remains: any goêtic path will, sooner or later, demand that we commune with spirits beyond the confines of ritual. In our work toward a co-created interspecies culture, spirits do not expect us merely to perform acts of orthopraxy at prescribed points in the lunar or solar calendar. Rather, they appear as lares and familiares — household gods and personal associates — who may surround us at any moment. And at any moment, they expect our human acts to be meaningful to them.

This is worth pausing on. If you have ever lived with a dog, you will know this dynamic. A dog assumes you are attempting to communicate with them at every moment — in how you answer the door, feed the family, sit or stand near them. All of it, in their eyes, is a language. Our relationship with spirits is no different, except that both parties alternate in the role of the dog. We observe one another, each convinced the other’s behavior is intentional speech. Let this sink in: spirits watch you like children or animals do, trying to read you in every moment. So what are you offering them up to see and sense, to draw meaning from?

I said, the abbreviated maxim of we are what we do is tabloid trash. Now, I am willing to offer a more nuanced version of this maxim as a starting point for our subculture-creation with spirits: What we do is what we speak.Here, “doing” is more than a physical act. It is the amalgam of the act itself, the manner of its crafting, and the reasons that impel it. The spirits perceive all three layers: the why, the how, and the what — or, in magical language, the devotion, the craft, and the seal.

V.

At the beginning, I described the common experience of the small world for many of us “by spending time in places we would rather not be and adopting attitudes we would rather avoid.” The small world runs on everyday necessities, mundane requirements and worldly imperatives. Most of all though, the small world hooks into each of us in the notion of duty.

In English, the word duty comes from the idea of being due something to someone — of owing an act or service. Its origin implies an external obligation: an outside force, be it law, authority, or custom, exerts pressure on the individual, and the required action emerges in response to that pressure. Duty, here is a reaction; the moment we encounter it, we are already on the backfoot.

The German word Pflicht, however, carries a very different root and spirit. It stems from pflegen — “to care for” — which implies not an imposed obligation, but an internal commitment. To fulfill one’s Pflicht is to tend to something as a gardener tends to a garden, a cook to a kitchen, a craftsman to a workshop. It is a duty born of relationship and stewardship, not merely of rule or debt. Here dynamic of the term is inverted, duty becomes an active choice.

The difference is obviously more than linguistic. Irrespective of our native language, we each get to decide whether we want to engage in fulfilling our duties in the small world as acts of willing obedience or cultivation of care. It doesn’t matter how tiny or seemingly insignificant our responsibilities might seem from the outside. Both, in magic and in wage labor, everything begins with attitude: How do we choose to relate to the people, powers, and places touched by our care.

In magical work, such difference will decide whether we perform a ritual because the calendar says so, or tend our altar because we sense its hunger for renewal. Equally, at work, we can show up once called upon to do as we were told, we can adhere to job descriptions, and timecards, or we can aim to see the whole of the work, from all functions’ perspectives, and beyond contributing our piece, aim to enable collaboration, synergies, and better understanding across everyone involved. The latter, would be a good example of us showing up as ‘bridge wardens’ at work, aiming to enable intentional passage, smart hand overs, and efficient partnerships among everyone.

I hope it is becoming clear how much coherence matters, when we step back and reflect on our appearances both in the small and the big world. The spirits who surround us — in daily life as in ritual — see no distinction between whether we are wearing grimoire sandals, business slippers, or sneakers. If we choose to accept, our goêtic mission is to make as much sense as possible in their eyes. And the central axis of that work lies in the values by which we steer ourselves. The more consistent and harmonious those values remain across our magical practice, our wage work, and our life with loved ones, the more clearly the spirits can see us — and the more meaning our actions will hold for them.

Let me put it another way: no one is eager to invest in an idiot who contradicts themselves at every turn and wears opportunism as a crown. What could we expect from such a partner in action? How much trust would we place in them? These are the questions the spirits are asking as they walk beside us, in the marketplace as well as in the temple: Are you worthy of my handshake? The answer is one we give every single day — whether we are doing heroic deeds, taking out the trash, or sit at a desk buried deep in routine. The way we hold ourselves determines how the spirits choose to hold themselves toward us.

In the third chapter, we spoke of the rope that binds us to the big world, even as we turn and wander within its cage. Let me bring this question up again here: What is it that prevents us from being wholly caged in by wage labor? Of which nature are these capillaries that can connect us — through the thickets of corporate life, of malls and retail shops, of fields and workshops — to the wilderness beyond the village fire?

Beyond the three anchors we have already explored — daily practice, regular meditation, and occult gatherings — this is my offer: it is our goêtically charged personal values, our goêtic ethos, that forms this rope. This guiding cord is always with us; whether we wear suits, overalls, sportswear, or ritual robes. We never ever relinquish it. It’s this ethos that we can turn into the strongest rope of all — one that reminds us to stand, “hüben und drüben zugleich - ein ganzer Mensch”, wholly present in both worlds, firmly rooted in the rock of our self, across all stages of our lives.

Sounds catchy enough. But what the hell does that actually mean when the rubber hits the road? How do I pull some kind of goêtic ethos out of thin air, Acher? That’s the kind of thing Acher-twenty-years-ago is throwing at me now. And he goes on: Make it concrete. I want it sharp, like a rock edge I can drag myself across until it throws sparks — sparks that might just light up my own values so I can actually see them.

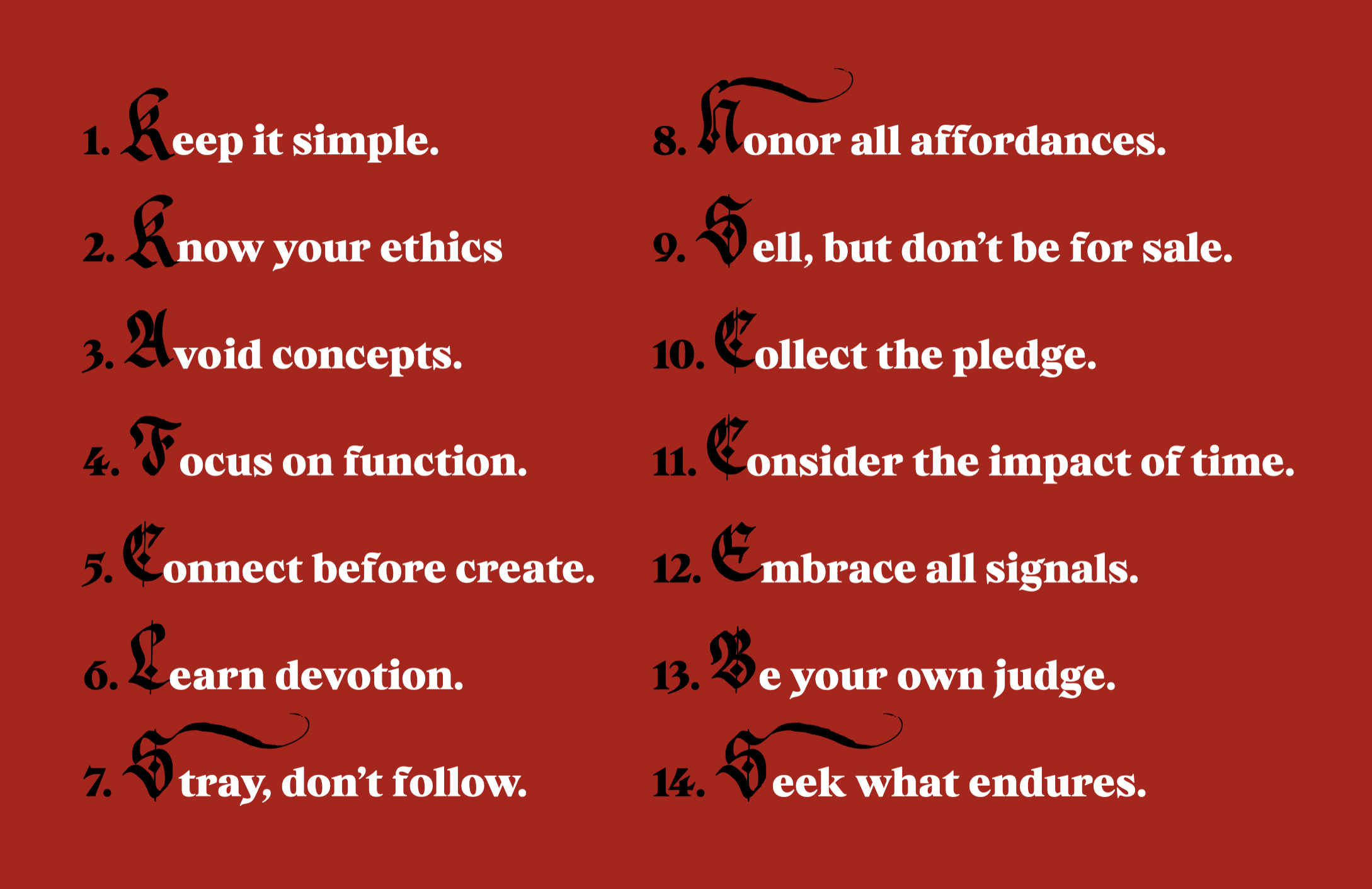

So allow me to be an obedient bridge warden to Acher-twenty-years-ago, and offer exactly that. On the next few pages, you’ll find my own current goêtic ethos, written out in fourteen points. I say current because these values are not frozen in amber — they are alive and mutating. The world changes quite radically; I change too, maybe a little less radical. On good days I stand a little higher now, and can cope with more complexity, more contradiction, more contrasts colliding with each other. On bad days, though I curse at the mess and need a clear answer. Then I pull that note from my pocket with my goêtic ethos on it, find the point that matters in that moment, read it once, and nod. I remember now; that’s it. And it’s back into the fray, with enough guts to assume my role as bridge warden again.

VI.

Goêtic Ethos

The following list of fourteen points has grown slowly over time. Some of them embody years of work, countless dead ends, and mistakes, until I could finally see clearly what the lesson was. Others practically leapt out at me. The seventh point, for example, is taken from a saying by Austin Osman Spare — about which I write at length in my book Goêtic Atavisms. Several others, especially points four, five, and nine through eleven, come from a 2023 interview the seminal tattoo artist, Filip Leu gave on the video podcast Books Closed. I can only wholeheartedly recommend it to anyone working to sharpen the whetstone of their own ethos.

What I want to point out here is this: our goêtic ethos is always mutating; sometimes in its periphery only and sometimes at its core. If we allow it, it will draw nourishment from all things we encounter — whether in the small world or the big. Just like the spirits’, the eyes of our ethos are always open.

What you see below is the simple list of the fourteen points, followed by a brief spotlight on each. May they offer a sufficiently sharp edge for you to rub against and refine your own guardrails of presence. May they serve you — whether in challenge or affirmation — in their own unique way, as they currently serve me.

LVX,

Frater Acher

Keep it simple.

There is a natural tendency when we begin to learn our craft to aspire to detail. When we arrive as a blank canvas, complexity easily appears to equal mastery. It takes a long time then to realize that simple often is quite the opposite of easy. The common ark of magical experience, thus, tends to carry us from naive innocence, to conceptual sophistication and further, if we get lucky, to well grounded simplicity. The goal is not to avoid this ark or to try to skip over necessary lessons; but to acknowledge that the truth changes.

Know your ethics.

Part of the beauty of the magical path is that we will get lost to ourselves many times. We will be not only challenged, but at a loss, as to who we are to this work, this world, this skin-suit we are caught in. Such stages of in-betweenness, of no longer being in our old skin and not yet having grown a new one, are the most profoundly creative experiences open to our species. They are charged with similar amounts of confusion, worry and pain, as with beauty, innovation and birth. On such high seas, it is natural to lose one’s bearings; no coastline remains in sight — only horizon, vastness, and the creeping fear of never arriving anywhere at all. To avoid regretting our actions in those moments, it is vital to carry a small set of ethical principles — self-chosen commitments, less than a code and more than nothing — that we are willing to honor even in states of deep confusion. It is worth considering early on: Which principles will steady your compass when you are lost again?

Avoid concepts.

This planet has seen countless brilliant minds with brilliant ideas — all eventually proven wrong. Having ideas is easy. Even crafting airtight, elegant theories takes less than we’d like to admit (especially in the age of GenAI). And yet, any bright concept says nothing about its value in lived practice over time. On the magical path, we navigate a realm invisible to most, where daemons speak in our own heads, and where kitchen accidents, road signs, nightmares, or offhand remarks might carry vital messages for rituals to still come or long passed. In such strange terrain, anyone smart can talk persuasive nonsense — including you and me. The best antidote to drowning in bullshit, hope-shit, or dream-shit (i.e., various forms of abstraction and self-deception) is still this: Let results lead. Trust only what works. Not the map you or anybody else drew before you got lost.

Focus on function.

No matter how highly specialized an ecosystem, a species, a body part, or even a single membrane may appear, everything in nature is dynamic. Nature reveals its inherent multiplicity not only through the continual reprocessing of matter (i.e., recycling), but especially through the fact that any given natural object holds dozens of different functions, depending on the perspective from which it is encountered.[1] Focussing on function then does not mean to explore how any non-human being might serve us or operate for our benefit. Instead, it calls for the sincere and ongoing exploration of the many diverse functions any single being can assume, depending on conditions, surroundings and relations. Focussing on function is a radical call to not be distracted by personal interest, moral convictions or aesthetic preferences. Rather, it is an open invitation for relational inquiry: Why does a given being appear the way it does? Whom does it serve? What nourishes it? What gaps would open without it? How does it behave in absence of (human) contact? And how does it respond when addressed? Focussing on function, from a goêtic perspective invites us to zero in on affordances. It invites us to throw ourselves into a world that is rooted in multiplicity and permeability instead of cause-to-effect instrumentality. So, before we can expect to extract any meaning, we have to become deeply entangled.

Connect before create.

Human creativity — in all its unruly, ugly, and glorious forms — is not a luxury. Rather, its a vital evolutionary tool that helps us to adapt to change, derive meaning from chaos, connect deeply with others, sustains our identity, and enables active participation in the mess that is this world. Yet our drive for creativity often can become a serious obstacle. For, it blurs the boundary between self and other, clouds our sight of what lies beyond, and narrows our focus toward expression instead of opening it toward unconditional impression. Connect before creation, therefore, is a call to decenter the self. It’s the simple principle to slow down, to pay respect to what already is, to breath for a moment in wonder, to recall the awe of otherness, before we pick up our own pen, before we lift our own torch, before we raise our own voice. Let’s face it: If our core intention is to be admired for what we have conceived, created, or composed, we won’t do well in goêtic practice. For this art requires us to see that all raw material is already artwork, that all substance is already accomplished, that our main job in many rituals is just to hold the gate open. Connect before creation is a reminder that on this path, the ability to create contact, not to create our own objects, is the expression of mastery. The world is already full — already meaningful, already mesmerizing. Our job often is actually not to add to it, but to enable better connectivity.

Learn devotion.

It begins with becoming still. Embracing the quiet. Then it proceeds to surrendering ourselves to a practice. To the knowing that we will fail, a hundred, a thousand times, in the pursuit of what can never be fully accomplished. Committing to a path without endpoint. To an open end. Not hasting towards praise, not rushing towards decorating our selves with more badges and insignia. To get up daily in humble submission. In loyalty to the craft. In the knowledge that our work is keeping something alive that breathes beyond us. Devotion is a hard thing to learn, for any human, at any moment in time. We are so afraid to remain without meaning, to not matter, to go unnoticed. All this fear we need to face, and then let go of, if we want to learn to live in devotion. If we want to embody genuine service. Facing our fear of insignificance, then turning around to serve in surrender, is not a singular act, not an oath, nor a pact. It’s a daily struggle, a grind, a raw rebellion, against the animal in ourselves that wants all for itself and everything now.

Stray, don't follow.

Roads — like primers, curricula, and grading systems — are instruments of reliable navigation and temporal efficiency. But they are not neutral. They are paths already scouted, memories of arrival hardened into rule. Above all, they are human-made. Roads and syllabi if not trafficked, blow over with dust, weeds and wildlife. They require passage to be seen. All trails disappear if not walked. In our art, we roam and relate with the anticumene and its strange ways of being. To travel through it, we must stray — through thickets and meadows, deserts and darkness — always haunted by the sense that we are lost and far off the tribe fires. We succeed when human orientation gives way. Scout bees fly alone. Wolves trace their own paths. The city fox avoids the intersections. If open roads led to the hare’s burrow, it would be worthless. Snakes and toads are wandering pioneers, and we do well to pattern our practice after them: to roam, to diverge, to stray, to meander without thread or master. What seems like indulgence or waste from the straight lanes’s perspective is, in truth, what tethers us to daemons.

Honor all affordances.

Every step is a barter. Even where no coins fall, we remain woven into the ubiquitous trade of giving and taking. This especially holds true in our goêtic work. We gain entry, we are invited to the table, we draw from the vitality of the non-human world — and how will we serve it in turn? What we offer as our affordance is not a matter of romance, tradition, or personal fancy. Currencies only hold when accepted by both sides. What we give in return for intrusion, exploration, and invocation must be useful to those we have called forth. On our path through an unchartered practice, we strive to leave no open accounts, no debts unpaid. We settle obligations as they arise, then move on with a light purse and swift step. This is an ideal of course, but one well worth pursuing. If unsettled dues catch us still, may our creditors know not as thieves, but fools.

Sell, but don't be for sale.

A long time ago, someone said to me: Not asking a price for your work is the clearest sign that you don’t value it yourself. Relying blindly on the hope that an equivalent return will find its way to you either means you’re very rich, or you're assuming a world without exploiters and bloodsuckers. Learning to protect our own affordances is an art we are all taught by way of cruelty and loss. This is especially true when communing with beings who hold no concept of the human species, and don’t know how limited our access is to renewal and the resurrection of what has once died. To give freely is noble; to sleep with an open purse is folly. As Felix Leu once said: We sell, but we are not for sale. Each of us sets our own price, chooses our clients, the hands we shake, the rivers into which our powers flow. This is the art of prudence: to barter and balance the scales, to stand in relation with beings we respect, and to place the pearls of our work in pockets and hands that know how to hold them.

Collect the pledge.

Just as some take too much, many never dare to take at all. Years of divine offerings, devotion to lares, candles lit for the dead – we all must collect the pledge. Personally, it took more than half a life to understand that in all relations — daemonic or human — we are bound to voice our needs overtly, if we want to avoid games of grudge and guilt. To pragmatically use our non-human alliances, to unapologetically involve our familiars, to break down the wall between the beyond and the mundane — it is a perilous path. It can easily obscure and cloud our sense of human agency and autonomy. Yet, we should allow ourselves to step onto it — calmly and with care — especially in moments when we are too alone to bear it. But to collect the pledge also means to honor the promises we make to ourselves. It means relinquishing the allure of martyrdom. It means unveiling the romance of the generous beggar, the noble donor, and the gentle soul for what it also can be: social kitsch — crafted by humans in power to paint submission as virtue. To insist that what was left open be closed, that what was offered be handed over, and that the body of a promise is its fulfillment — this, too, is the art of prudence.

Consider the impact of time.

Time poses one of the greatest challenges in practical magic. Once we step outside the boundaries of physical reality, time takes on an entirely different quality. At least in my experience, it is impossible to make statements about time in the magical realm that are as one-dimensional as those in the mundane world. I have encountered places where time flowed backward, where it ceased to exist altogether, and where historical events unfolded simultaneously in a single, overwhelming moment. Like many, I’ve also witnessed situations in which temporal disjunctions occurred — ritual outcomes manifesting before the ritual itself had taken place. When we act in the magical realm, we must remain acutely aware that cause and effect do not move in a straightforward line. Just as important is the understanding that there is no inherent reason why an effect should appear within the same timeframe as its cause. Often, the consequences of our magical actions become visible only months, years, decades — or even incarnations — later. This should serve as a warning against the temptation to “press all the buttons” and, when nothing happens immediately, to press some more. Rather than imagining magic as a technical switchboard, it is helpful to think of it as the planting of seeds or the introduction of living organisms into our system — inoculations, if you will. These living influences may take years before their effects are felt within and around us — if we are observant enough to notice them at all. And just as with real immunizations, once these effects take hold, they are often extremely difficult to reverse or neutralize.

Embrace all signals.

No moment is too small. Even a knocked-over glass invites us to revisit The Discipline of DE. Every ordinary day is full of stimuli — nudges, slaps, jolts, and glimpses into distorted or painfully accurate mirrors. All of these are chances to learn, to grow, and, through reflection and experience, to bring our actions into greater harmony with the world around us. None of this changes the fact that we all have the right — and are sometimes well advised — to give the world the middle finger. The freedom to reject unsolicited feedback is just as essential as the humility to admit when we are wrong. What matters is avoiding the impulse to bury lessons under layers of ego, excuse, or performance. Admitting fault, breaking habits, and stepping aside for our better selves is hard enough in daily life. How much harder is it, then, when we are not offending uncles or aunts, but daemons and angels, celestial gatekeepers and underworld dwellers? The list of beings to whom our ritual actions appear callow is much longer than the list of all rituals we’ve ever performed. To embrace all signals, thus, means keeping our perception sharp. It means constantly seeking out new data — new patterns, new vistas — to expand the body of knowledge we have available for future behavior. It means valuing insight over image. To learn from all signals means to seek growth over the need to be right, to look good, to be liked, or to retain control. To learn from everything is to live out our best Dr.Faustus — curious, relentless, uncompromising — everywhere, most of the time.

Be your own judge.

Easiest to say, hardest to do. We are wired to feel vulnerable, to crave validation, to dread isolation. That’s part of the human condition for all of us. But for the practicing magician, it can turn into a lifelong crucible. Witches lived at the far edge of the village for a reason. You cannot have both: the freedom to pursue semi-taboo arts in a culture still steeped in Christian values, and the regular tip of the hat, clap on the shoulder, and warm welcome at the local pub. Even among practicing Western magicians, a community even smaller and more scattered than the shards of a broken scrying bowl, the default response to most new ideas is a frown, combined with a raised index finger, pointing at some books that somewhere along the way, ossified into undisputed truth. I suggest you rather keep it with Paracelsus, serve no one if you can be a free wo/man. If that was your choice, however, being your own judge will be the natural price - for what you want more or less of, for which risks you are willing to take, and for what you will give yourself genuine recognition.

Seek what endures.

Yes, I know. This final one could invite for endless philosophical speculation. But that’s not the point I am trying to make; I probably simply worded it badly. What I mean to say is: each thing that captures my attention, that stirs my emotions, that is ready to invade my circle of time – let me examine it, how ephemeral or permanent it is. The more permanent, the more it might be prudent to grant it attention, to invest in emotionally, and to open my circle of time to it. The more permanent, the more affordance I am generally willing to offer up to it. The more ephemeral and fleeting, short-lived and momentary, the more I might want to guard myself from swallowing its bait. In this sense, seeking what endures, is not an existential statement, but one anchored in time: seek those things that stand a little longer in time, that aren’t washed over in the next hour, the next day, the next year. Seek islands of at least temporary permanence. I am slow and certainly not the smartest. My mind functions best when granted a little more time to encounter, relate, and test its responses.

Footnotes

[1] As an example, we can return to the dynamic function of membranes: Cell membranes might seem like clear-cut boundaries, selectively allowing passage of molecules. Yet they are also sites of chemical communication, hosts to viral docking processes, and even mechanisms of identity (through surface proteins). Their function depends entirely on context: a membrane protein might be a receptor, a signal, or an entry point for a parasite. Again, function is never singular, and never static.